Published June 2022, Plastikcomb Magazine issue #4 (sold out)

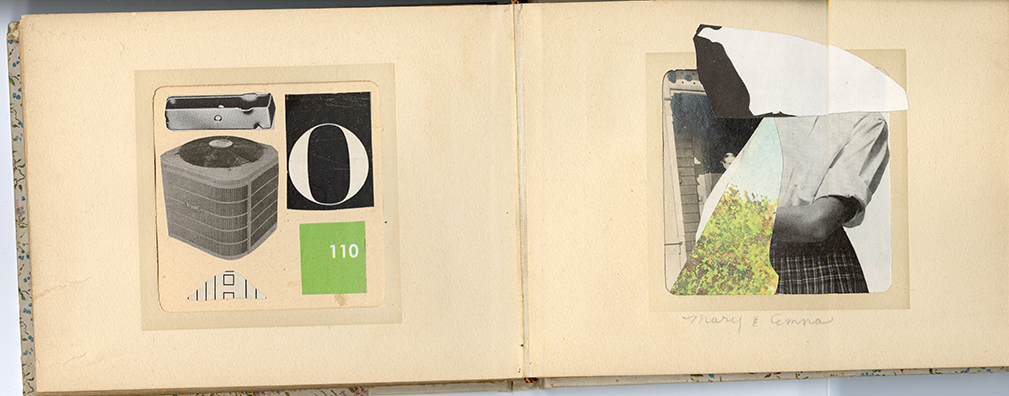

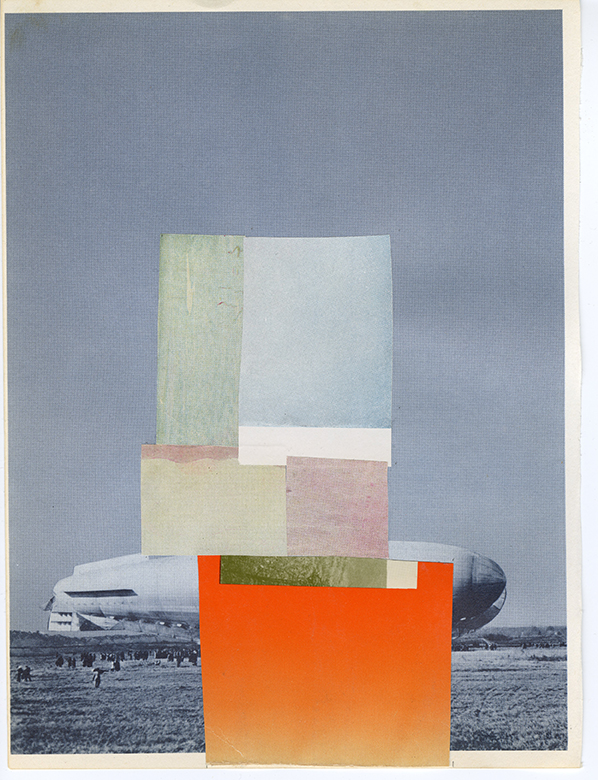

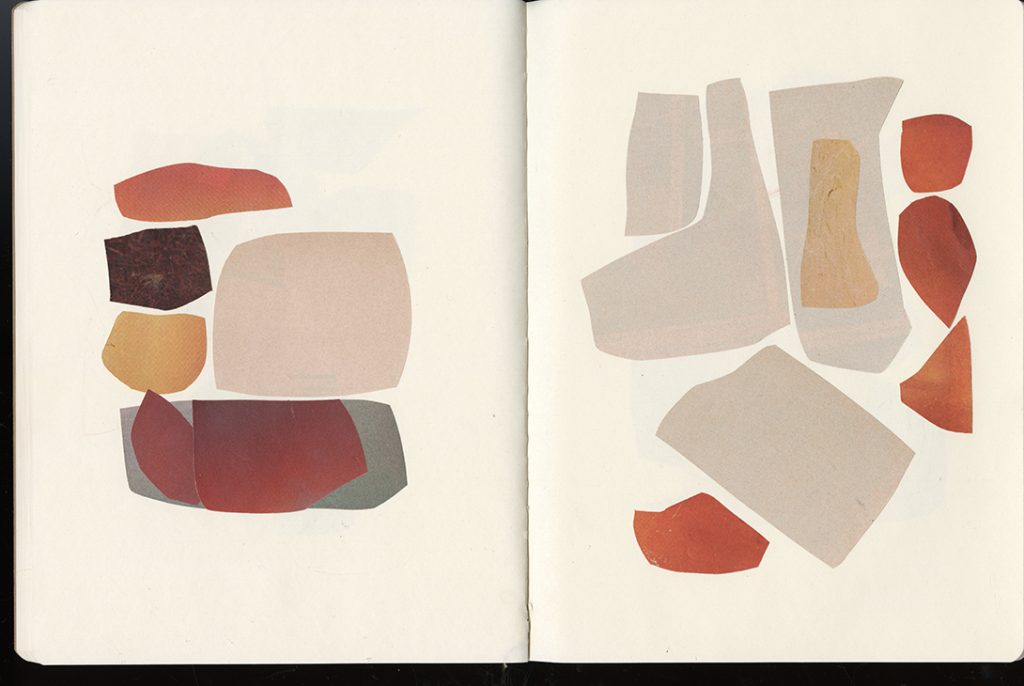

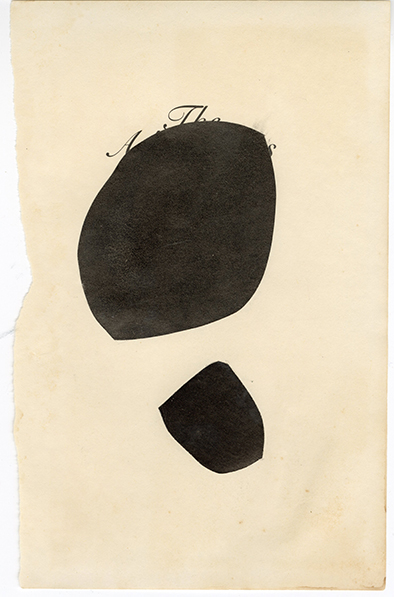

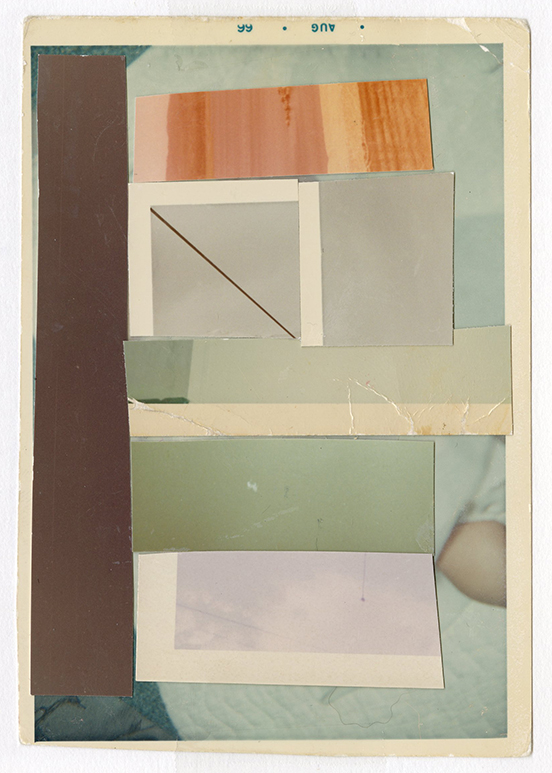

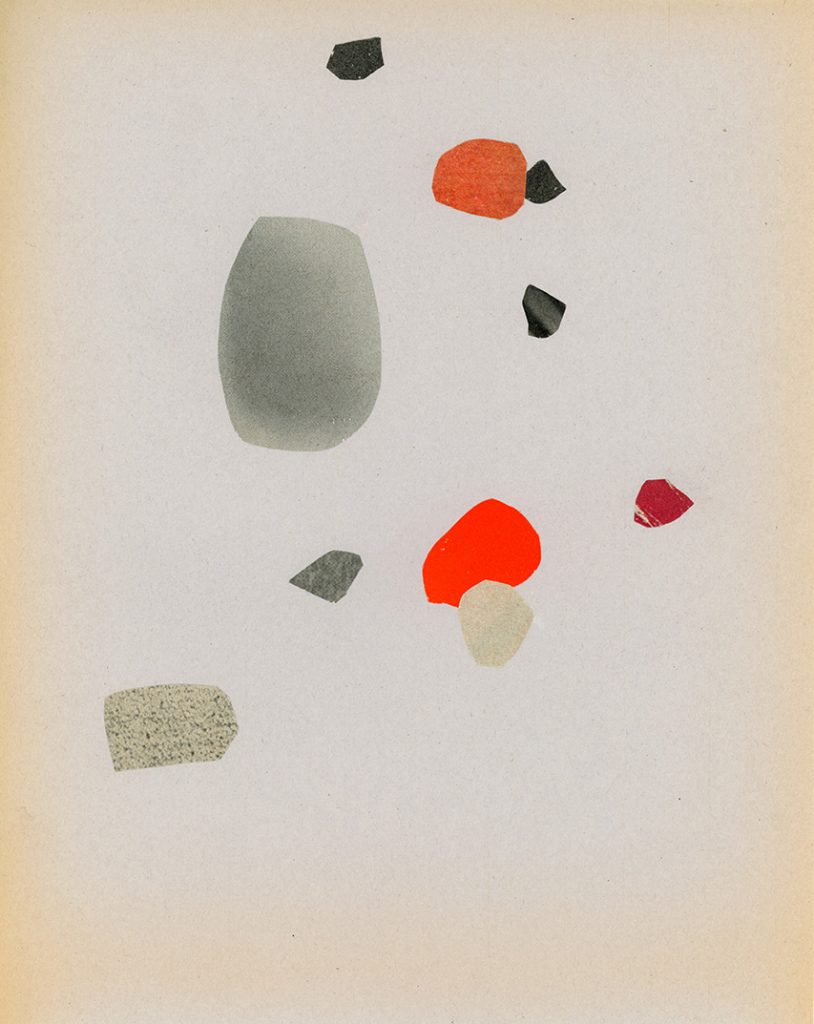

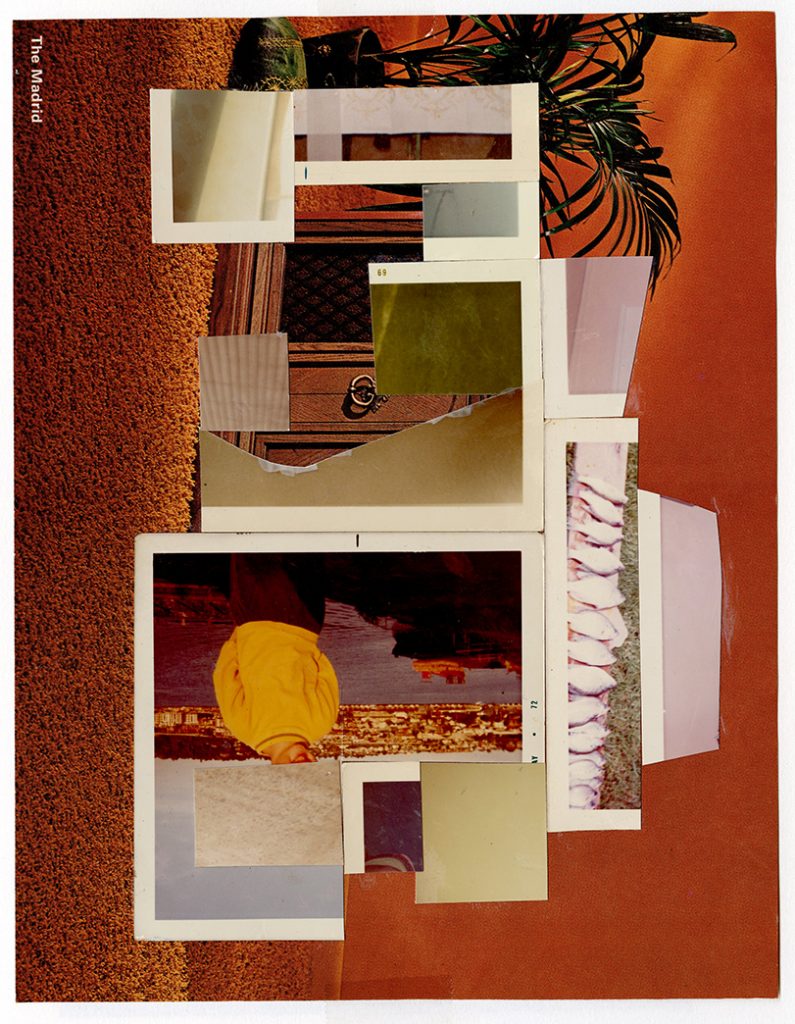

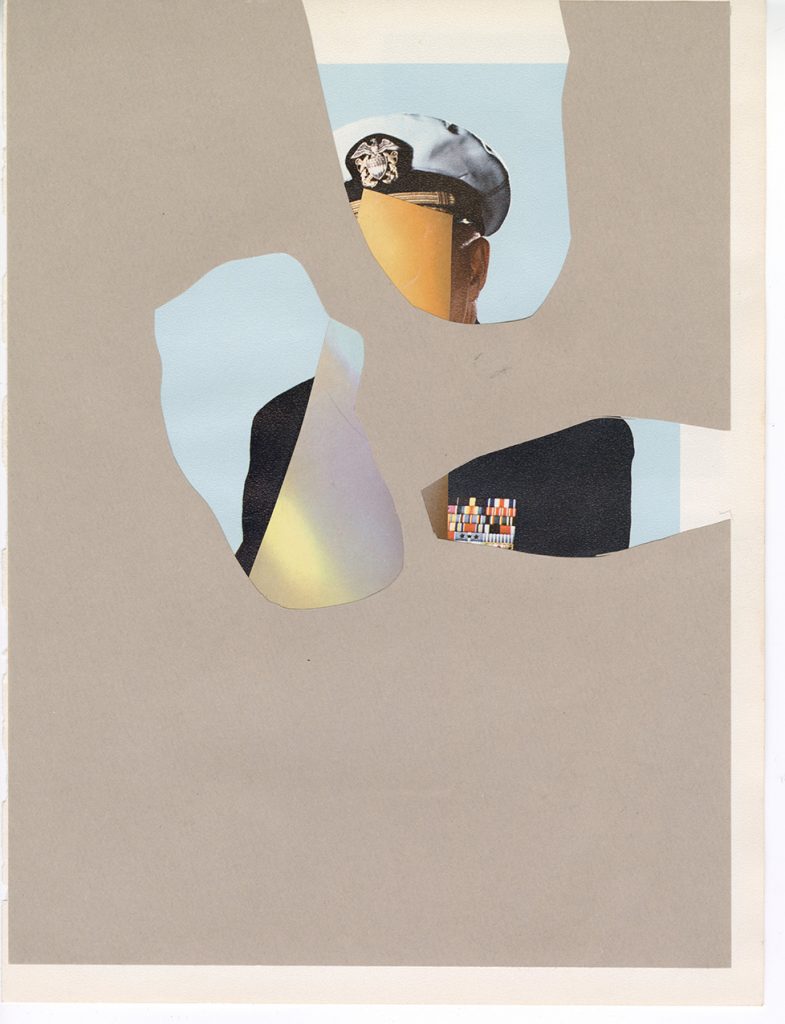

Muted tones, powder colors; noticeable patina of senescence as only ochre, shell pink, newsprint gray, washed-out greens, blues, mustard yellows, faded, and deteriorating material can deliver. Bolder hues and fabrications that oscillate between garish, kitsch, lurid, amusing, idyllic, industrial, and grotesque are scattered but, all in all, John Gall’s collages evoke the unhurried, flickering playback of celluloid memory, grammar school readers, a vastly different and saccharine, pre-20th-century US.

These are the worlds Gall has so far written, for what are collages but matters of phrasing? Ways of reconstituting abandoned raw material, a means to revitalize and give new form to someone else’s effects. One might like to call Gall’s decade-long cut paper oeuvre “vintage”, but that adjective is an unreservedly hollow designation. “Vintage” falls short of what his handiwork could represent to viewer-readers willing to expend the visual and cognitive capital warranted by his orchestrations. Indeed, wonder or amusement (or frustration) about Gall’s collages stem from reasonable attempts to discern their sum and substance. To say that he has a penchant for imagery or that his eye for imagery is “remarkable” or, that he is an “accomplished” collagist would be pat – statements of towering obviousness that serve only to foreclose probing Gall’s fastidious curation and craftsmanship (by day, he is Creative Director at Alfred A. Knopf where he oversees a gargantuan 200+ cover designs a year).

In the publication John Gall Collages 2008–2018, he states, “Instead of trying to make visual connections between images – building metaphors and communicating these connections with some level of clarity … collages became a way to distance myself from [the conventional] practice [of graphic design], a way to lose connections and disrupt my own expectations.”

Could a veteran graphic designer silence his analytical, sense-making frame of mind? Could he willfully abandon “picture making” which embodies intent, for unfettered, and decidedly self-serving visual exploration? (Gall admits to having been “in a creative rut” and that the “purely visual exercise” of collaging was a needed break from the unflagging exigencies of book cover design.) Could he, in actuality, supplant his tendency toward synthesis, relation, arrangement, connotation, denotation, and bias for “saying something” by dint of elemental fabrication? These are inescapable questions that call attention to the real or presumed divide between art making and commercial design practice (i.e., the business of supplying visual solutions for the benefit of individual clients, organizations, industries, or institutions).

In Pieces

Collage was an early 20th century invention promulgated by Pablo Picasso and George Braque. While the telltale combination of found material (e.g., newspaper clippings, advertisements, wallpaper, sheet music, cut pieces of paper, fabric, etc.), hand-rendered imagery, textures, and verbiage were undoubtedly revolutionary, the most transformative byproduct of collage was its deprioritization of perception. Collage excised the attendant anxiety of “correct” representation which, in turn, liberated and enfranchised artists to exploit and recast reality. Indeed, the medium’s “slice, suture, reassemble”* approach was a perfect match for the speed and transformation that characterized Picasso’s and Braque’s Paris, a period replete with printed ephemera, the very ingredients they sought and skillfully deployed. Collage’s hallmark cut-and-pasted front was also a reflection of burgeoning consumerism and its concomitant mercuriality: meanings and loyalties were negotiable and subject to the way information was pieced together. Thus, images were less about facts and truth-telling; they were, instead, reflections of an artist’s imagination.

Absent the economic, artistic, and socio-political circumstances that prompted a collage revolution notably, those produced by the Futurists, Dadaists, Surrealists, and Pop Artists (ca. 1905–1960s) who took their cues from Picasso and Braque and whose goals were, variously, to institute change, expand knowledge, broaden perspectives, halt cruelty, magnify perceptions, or speak truth to power, collage has since achieved such ubiquity that it often goes unnoticed. From circulars to online marketing, fashion styling to sampled music, from “Chinese food” to global cuisine, jazz fusion to super groups, from daydreams to the manifest cutting, pasting, and editing facilitated by word and image-editing software, everyday life is soaked in collage.

Gall’s body of collages adhere to the historical blueprint. Made from sundry printed materials that have been cut with scissors and glued onto newsprint or plain white paper, each is evincive of his preference for exploiting “unimportant and not particularly attractive material” that “happens to be vintage…. Readily available and inexpensive.” Thrift shops, curbsides, and library book sales are his favored venues and so vintage-ness is a corollary, not an aim, of Gall’s archeology, a working condition that relies heavily upon the rewards or poverties of time and place. Though Gall considers collages a “personal outlet”, each is a treasury and a display of great invention.

Messages or meanings, if any, are moot. By Gall’s own admission, “I really have no interest in creating a collage with any sort of literal or narrative structure. I also don’t have a story to tell.” And yet, there is much to see and, for the contemplative viewer-reader, much to ponder. Perfunctory compositional maneuverings notwithstanding, it is Gall’s unassailable visual literacy, his gift for recognizing graphic possibility that comes to the fore. His ability to “read” what images concretely portray and wherewithal to detect veiled pictorial properties trigger unanticipated connections and extraordinary juxtapositions.

In defiance of his own impassivity (he tells stories, though they are, perhaps, not the kind he considers to be especially noteworthy), Gall’s methods are demonstrably beguiling and inventive. He fluently and constantly engages the elemental grammar of art through placement, layering, contrasts of scale, of texture, weight and structure (i.e., shapes and outlines), the latter being the net result of his peculiar interventions, the way he extracts, detaches, and transplants components from their natural habitats, scissors in hand, uninhibited by plan or prejudice. The stories he tells are of possibility. The way he splices, trims, retrofits, and reorders extricated components are the story and, that story is a testament to what one can achieve with one’s eyes, one’s hands, and one’s imagination (i.e., without aid and albatross of Planning but with astonishing prescience).

Taken as a whole, Gall’s collages amount to an axiom, a way of crafting images that fly in the face of conventional visual production. This magnitude of seeing – his capacity for detecting pictorial consanguinities and complexions – belie his sangfroid assurance of narrative privation. His collages refuse to resolve and, whether or not they are acts of design or of art; whether or not they really are spontaneous are beside the point.

They are passage. To where and for what reasons?

Keep looking.

*Farago, Jason. “An Art Revolution, Made With Scissors and Glue.” The New York Times, 29 January 2021, www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/01/29/arts/design/juan-gris-cubism-collage. Accessed 1 November 2021.